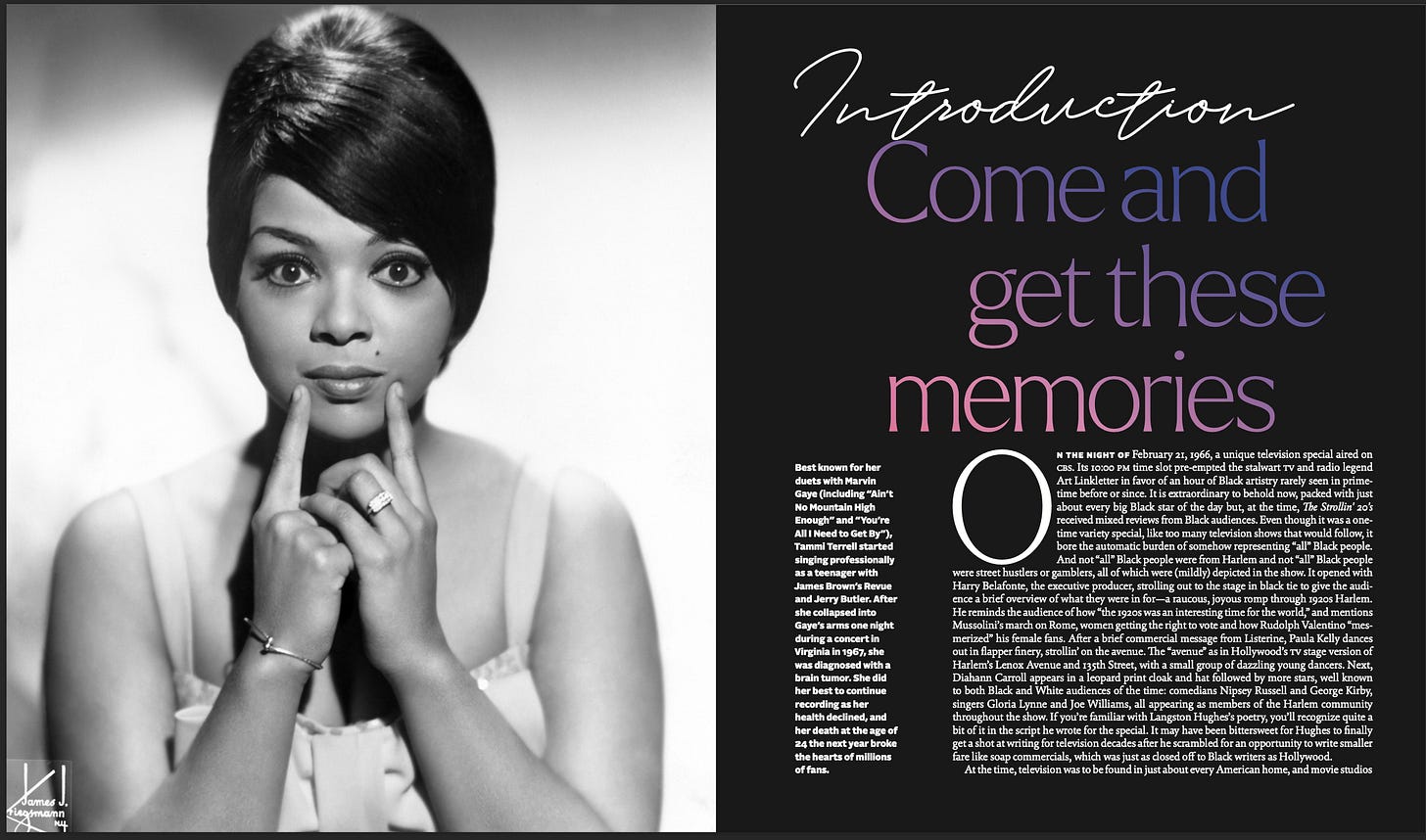

The introduction pages from my book, Vintage Black Glamour: Encore, featuring Tammy Terrell.

On the night of February 21, 1966, a unique television special aired that showcased an hour of Black artistry rarely seen in prime-time before or since. It is extraordinary to behold now, packed with just about every big Black star of the day but, at the time, The Strollin’ 20’s: a Celebration of the Harlem Renaissance, received mixed reviews from Black audiences. Even though it was a one-time variety special, like too many television shows that would follow, it bore the automatic burden of somehow representing “all” Black people. And not “all” Black people were from Harlem and not “all” Black people were street hustlers or gamblers, all of which were (mildly) depicted in the show. The show opened with Harry Belafonte, the executive producer, strolling out to the stage in black tie to give the audience a brief overview of what they were in for - a raucous joyous romp through 1920s Harlem. He reminds the audience of how “the 1920s was an interesting time for the world,” and mentions Mussolini’s march on Rome, women getting the right to vote and how Rudolph Valentino “mesmerized” his female fans. After a brief commercial message from Listerine, Paula Kelly dances out in flapper finer, strollin’ on the avenue. The “avenue” as in Hollywood’s TV stage version of Harlem’s Lenox Avenue and 135th Street, with a small group of dazzling young dancers. Next, Diahann Carroll appears in a leopard print cloak and hat followed by more stars, well-known to both Black and White audiences of the time: comedians Nipsey Russell and George Kirby, singers Gloria Lynne and Joe Williams, all appearing as members of the Harlem community throughout the show. If you’re familiar with Langston Hughes’s poetry, you’ll recognize quite a bit of it in the script he wrote for the show. It may have been bittersweet for Hughes to finally get a shot at writing for television decades after he scrambled for an opportunity to write smaller fare like soap commercials, which was just as closed off to Black writers as Hollywood.

I was so happy to get this photo in my book for posterity: The stars of “The Strollin’ 20’s: a Celebration of the Harlem Renaissance.” From the back (l-r): Sidney Poitier, Langston Hughes, Harry Belafonte, Joe Williams, Nipsey Russell. Front (l-r): George Kirby, Gloria Lynne, Diahann Carroll, Paula Kelly, Duke Ellington. Below, Mr. Ellington is flanked by Ms. Carroll and Ms. Kelly. Both photos were taken by Rowland Scherman - who has Substack account (!) where he talks a bit about being assigned to photograph the show for LIFE magazine in 1966.

By this time, nearly every American home had a television set and movie studios felt the loss at the box office as most people got their entertainment from the comfort of their own living room. In the wake of Bonnie and Clyde stunning Hollywood with its success in 1967, Time magazine published an article with the title, “The New Cinema: Violence…Sex…Art.” In it, the writer noted how never-before-seen, or at least truly seen, gradations of violence, sex, and art were starting to show up in the movies. Milquetoast offerings like retread musicals and chaste romantic fantasies were being pushed out for edgier fare. Yet and still, these were the days when guests and hosts could and did drink and smoke on the air and there were many conversational, salon-like talk shows. In one such space, the can-do-anything-man, Sammy Davis, Jr., had a talk show and one night, Diahann Carroll and Redd Foxx were his guests. Sammy mentioned how Carroll’s milestone show, Julia, was criticized as unrealistic and Redd Foxx admitted that he had some of the same reservations, saying, “…she’s in a $300 gown and I figured she must be selling dope from the back…” Even superstars like Sammy Davis, Jr. and Redd Foxx found it hard to “relate” to Julia. Maybe it was the Diahann Carroll-ness of Julia that made it hard to suspend disbelief at a Negro nurse “cleaning up really nice” in an evening gown in 1968. What was she expected to look like? How was she to present herself so she would look more “believable” as a Black nurse who was also a single mother? I would have loved to have gotten Davis’s or Foxx’s take on the film Nothing But a Man (1964) and I would have really loved to have witnessed and experienced the cultural impact it could have had on Black people who were still racing to the telephone in this era to call people whenever a Black person appeared on television. The limited release of that move and other art that made earnest attempts to show Black people in their full humanity prevented that from happening, even with stellar performances by Abbey Lincoln and Ivan Dixon and a soundtrack from the then hot and new Motown Records, a rarity for any move of that time. If you were “Young, Gifted and Black” during this era, you may have been amongst Black students who were demanding Black studies (history and people purposely left out of American school books for generations) at Black colleges. You may or may not have even heard about “Nothing But a Man” unless you were “in the know” or lived in a big city with access to smaller, indie films. You may or not have been home on that Saturday night in February when The Strollin’ 20’s aired.

By the time I saw The Strollin’ 20s, it was already the 21st century and I (born three years after the special aired in 1969) was already past my fiftieth birthday and had written two books (now three) highlighting as many Black legends as I could. I have spent hours upon hours of my life sitting in libraries with headphones on, listening to and watching history, but it was rare to be as enthralled as I was that day. I had always only heard or read about television or Broadway shows of yore that I would never be blessed to see because they were not recorded or, the recordings were buried away with other priceless historical events (like the Summer of Soul concert that only saw the light of day a half century after it took place).

Thankfully, quite a bit has surfaced over the years on YouTube, but some will forever remain tucked away in dusty archives or, at worst, lost to later generations. Posterity, in a world where books are still actively banned and history is aggressively being erased or rewritten, is no small thing and it will never get old for me.

Nothing But A Man is on the Criterion app, I'll be watching this tonight